India’s Defence Sector: From Dependency to Dominance

India’s Defence Sector: A Strategic Evolution

India’s defence sector has undergone a remarkable journey—from the early days of independence when the nation scrambled to equip its forces, to a modernising ecosystem striving for self-reliance today. This origin story is filled with challenges, strategic choices, and transformative reforms. It’s a narrative of how a young country forged its defence capabilities, initially under the shadow of foreign dependence and later through indigenous resolve.

Origins: Post-Independence Challenges and Early Dependency on Imports

When India became independent in 1947, it inherited a fragmented military infrastructure reliant on WWII-era British equipment. The new nation’s immediate priority was defending its sovereignty, but it lacked a native arms industry. Facing partition and regional conflicts, India had to import rifles, artillery, aircraft, and naval vessels to arm its forces.

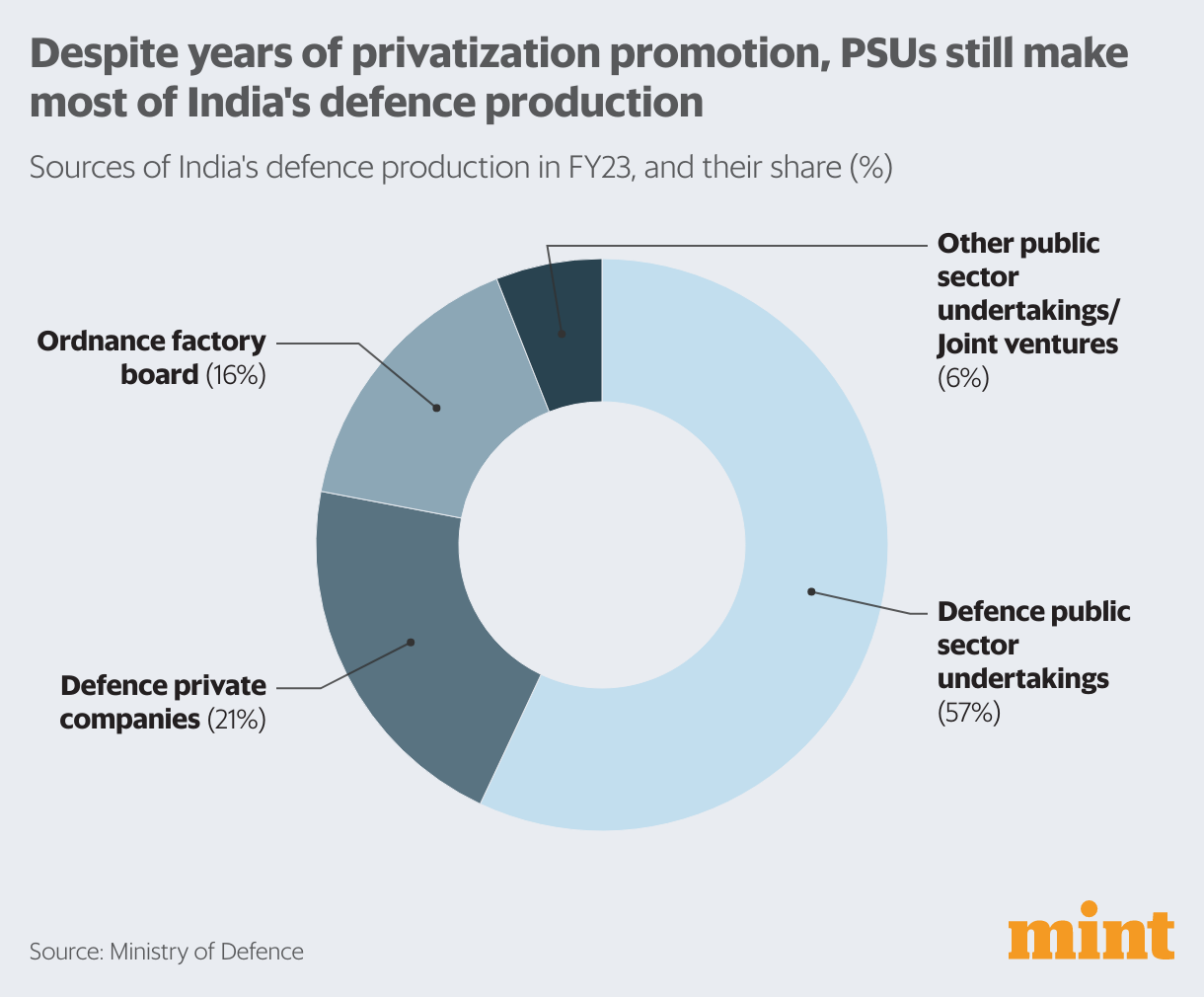

In the 1950s, India’s leadership, notably Prime Minister Nehru, emphasised self-sufficiency and industrialisation. Initial steps were taken to build a domestic defence production base, but progress was slow. A 1956 policy reserved defence production for the public sector, effectively excluding private companies for decades. The establishment of DRDO in 1958 signalled a more structured approach to R&D, while state-run firms like HAL were nationalised and expanded.

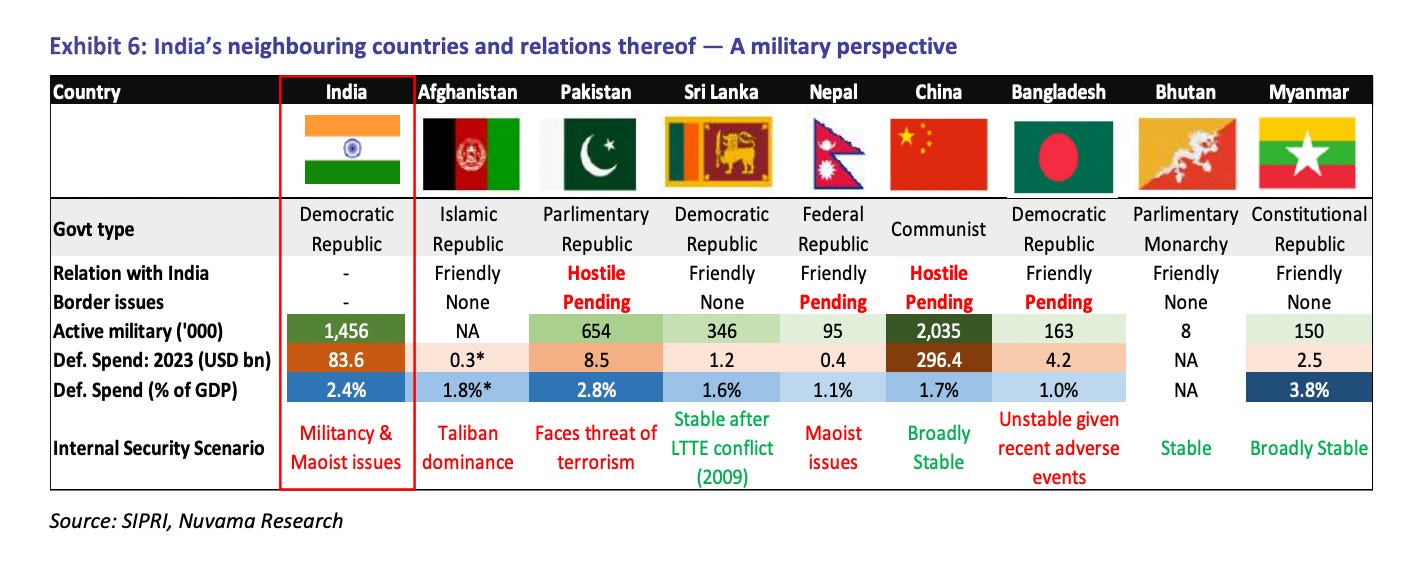

Despite these efforts, foreign reliance remained high. India imported advanced systems from the UK, France, and later the Soviet Union. The 1962 war with China was a wake-up call: under-equipped Indian forces faced defeat, leading to a boost in defence spending. The 1965 and 1971 wars with Pakistan further strained India’s arsenal, pushing it closer to the USSR, which became its primary supplier of high-end military hardware.

The Rise of Public Sector Dominance: DRDO, HAL, and Indigenous Ambitions

From the 1960s to the 1980s, the sector was dominated by public-sector entities. Companies like HAL, BEL, and the Ordnance Factories were tasked with delivering everything from small arms to fighter jets. This era saw several indigenous projects—HF-24 Marut fighter, Vijayanta tank, and the launch of the Integrated Guided Missile Development Programme.

Ambitious initiatives like the LCA Tejas fighter and the Arjun Main Battle Tank emerged. However, these programs were plagued by delays. Indigenous systems, while symbolically important, often became outdated by the time they entered service. Meanwhile, the Soviet pipeline kept India’s armed forces running. The public sector, with its guaranteed orders, suffered from complacency and inefficiency.

By the 1990s, it was clear that India’s strategic aspirations were far ahead of its industrial capabilities. Despite decades of investment, around 70% of major defence hardware was still imported.

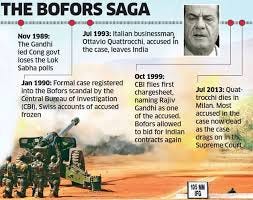

The Long Shadow of Bureaucracy and Policy Inertia

The post-Bofors era of the late 1980s introduced a deep fear of scandal, slowing procurement to a crawl. Defence acquisitions became multi-year marathons with little guarantee of completion. Insular policies further restricted innovation—private firms were excluded, and DRDO was left to deliver across a vast mandate, even in areas outside its expertise.

Key structural reforms like the creation of a Chief of Defence Staff, proposed decades earlier, were delayed for years. The Kargil War in 1999 exposed critical preparedness gaps. While the armed forces prevailed, post-conflict reviews criticised procurement delays, inadequate gear, and systemic inefficiencies.

Strategic Shifts Post-Kargil: Modernisation and Reform in the 2000s

The turn of the millennium marked a pivot. The Kargil conflict catalysed deep reviews and reforms. A formal procurement framework was introduced, defence budgets rose, and modernisation took centre stage.

In 2001, private sector participation in defence manufacturing was allowed for the first time, albeit with restrictions. Indian industrial giants like Tata, L&T, and Mahindra began entering the space. Co-development projects—such as BrahMos with Russia—showed promise, while direct imports like Su-30 MKI jets and UAVs addressed immediate capability gaps.

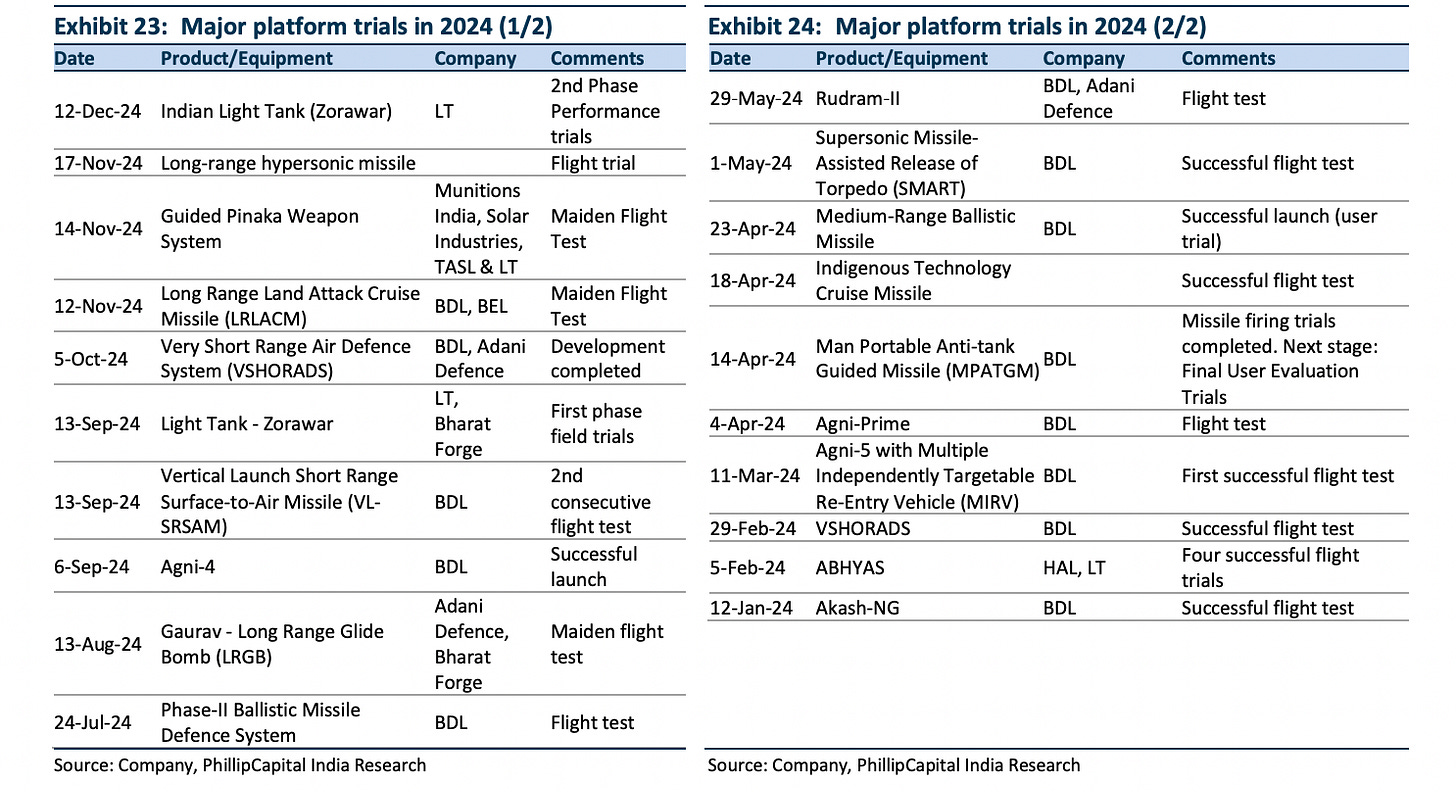

DRDO and HAL achieved some successes—the Agni missile series became operational, and the Tejas prototype took its first flight in 2001. The Navy emerged as a leader in indigenisation, beginning construction of the INS Vikrant and a new class of indigenous frigates and destroyers.

The Modi-Era Push: Make in India and Atmanirbhar Bharat

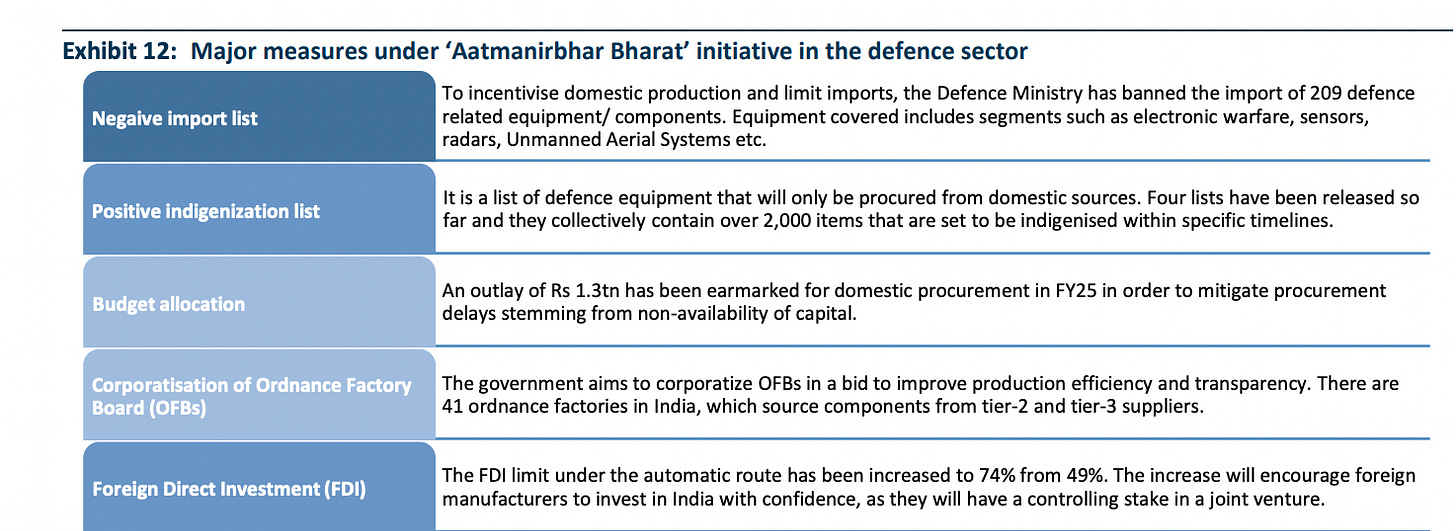

In 2014, the launch of “Make in India” gave a fresh thrust to domestic defence production. Defence was identified as a priority sector, and foreign manufacturers were encouraged to build in India. Later, the Atmanirbhar Bharat initiative amplified this push, setting clear import bans and encouraging innovation.

A landmark move came with the publication of the “negative import list” – a catalogue of items the military would source only from Indian manufacturers. This effectively created a guaranteed demand pipeline, offering massive opportunities for domestic firms.

The ecosystem approach also changed. Innovation programs like iDEX encouraged startups and MSMEs to co-develop solutions with the military. The message was clear: India must not only make but also invent in India.

Key Reforms and Policy Overhauls: FDI, Procurement, and DPSU Revamp

To support this vision, FDI limits were liberalised—first to 49%, and then to 74% under the automatic route. Global players like Lockheed Martin and Kalashnikov formed JVs in India.

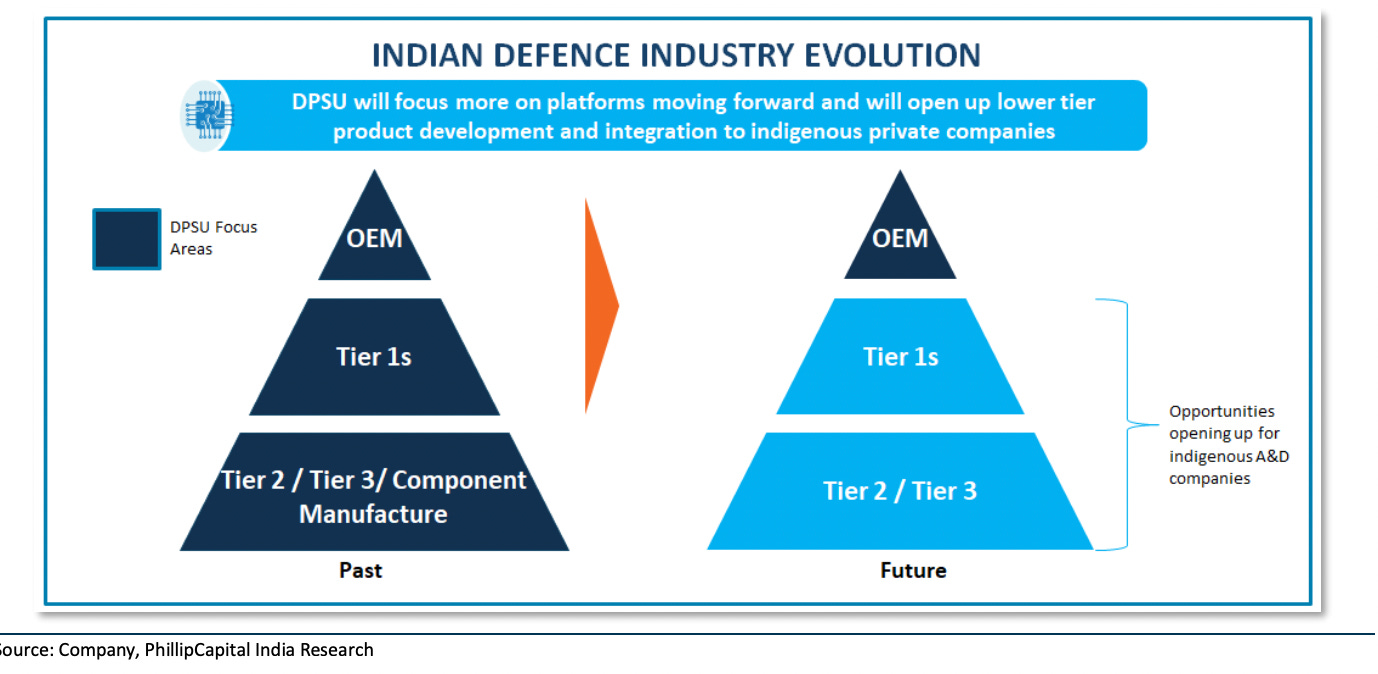

Defence procurement policies were overhauled with the Defence Acquisition Procedure (DAP) 2020, which prioritised Indian-designed and developed systems. Startups and private firms now have access to funding and procurement pipelines previously limited to public sector behemoths.

The restructuring of the Ordnance Factory Board in 2021 into seven new corporations introduced much-needed accountability. These new DPSUs quickly turned profitable, began pursuing export orders, and were directed to invest in R&D.

Rise of Private Players: A New Era of Indian Defence Industry

Private defence manufacturers are no longer on the periphery. L&T delivered the K9 Vajra howitzer ahead of schedule and has been integral to submarine projects. Tata’s partnership with Airbus is producing the C-295 aircraft in India. Bharat Forge not only co-developed the ATAGS artillery gun but has also exported it to Armenia and a European customer.

These firms are building confidence within the armed forces and proving that Indian private industry can deliver strategic systems efficiently. HAL and other DPSUs are stepping up their game, entering export markets and investing in new platforms under competitive pressure.

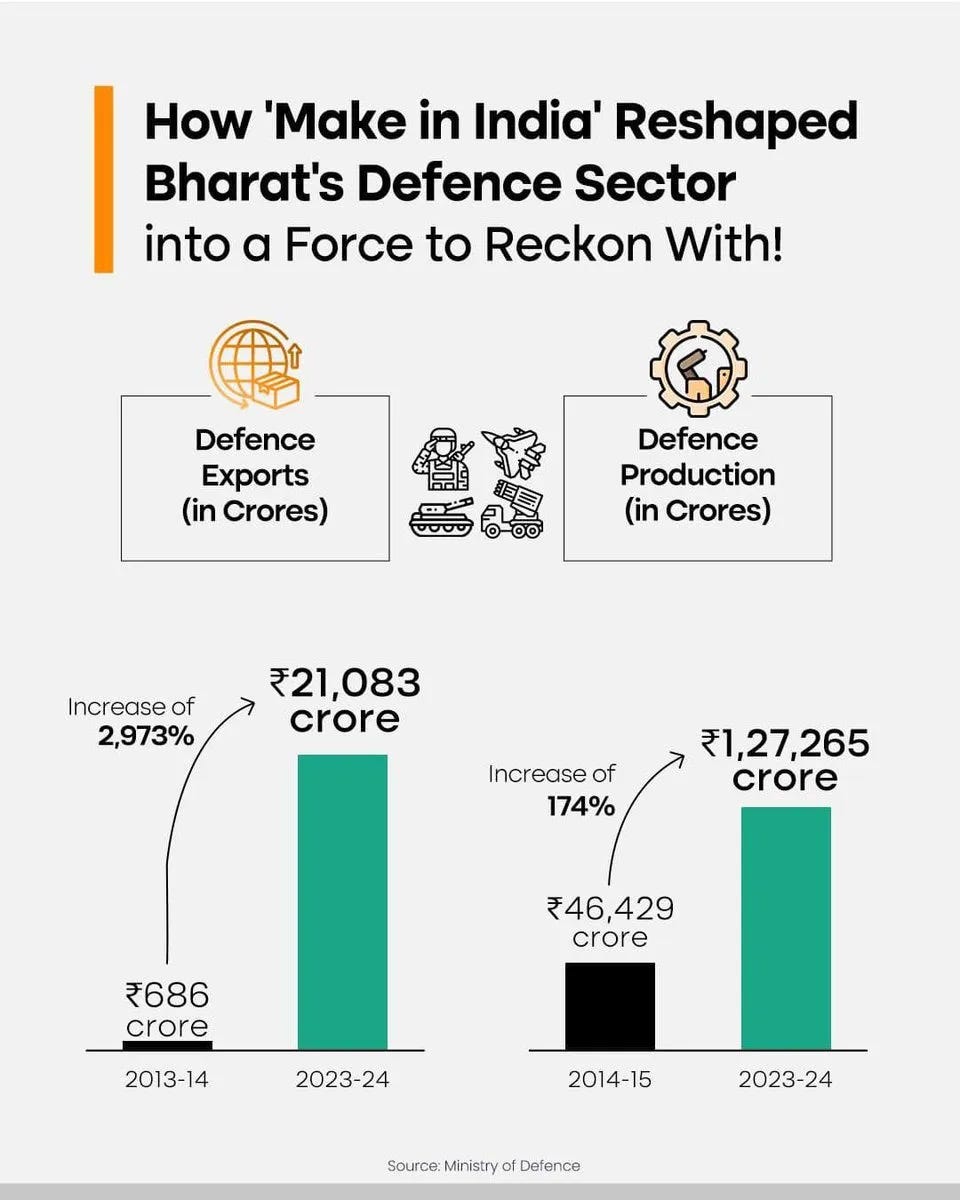

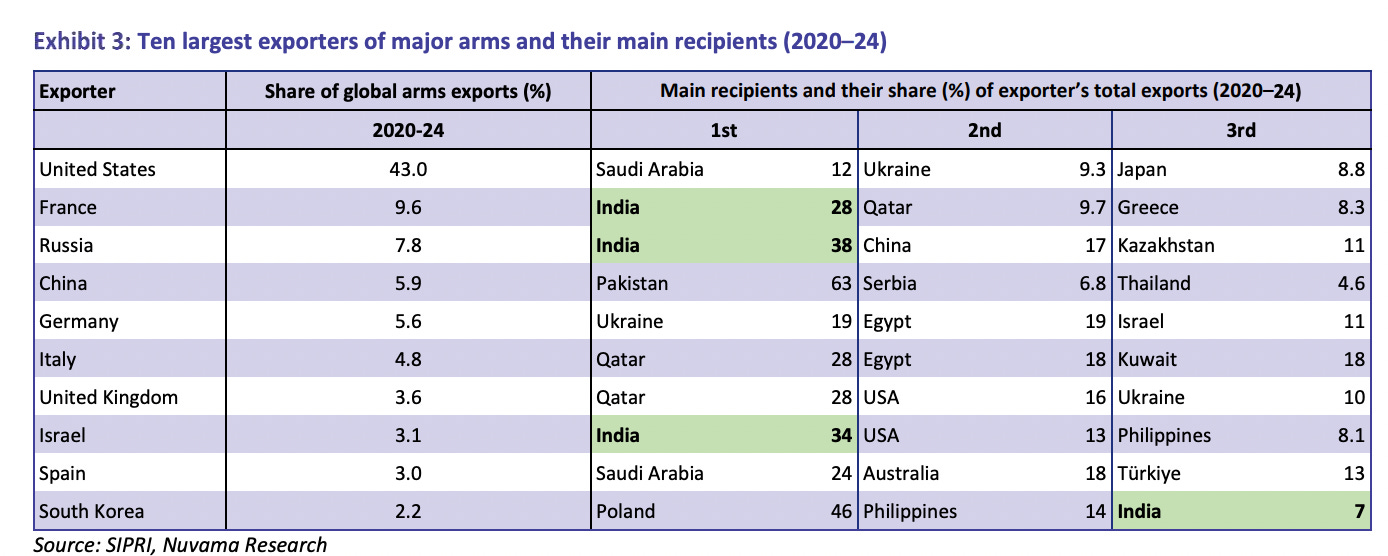

From Importer to Exporter: Defence Exports Surge

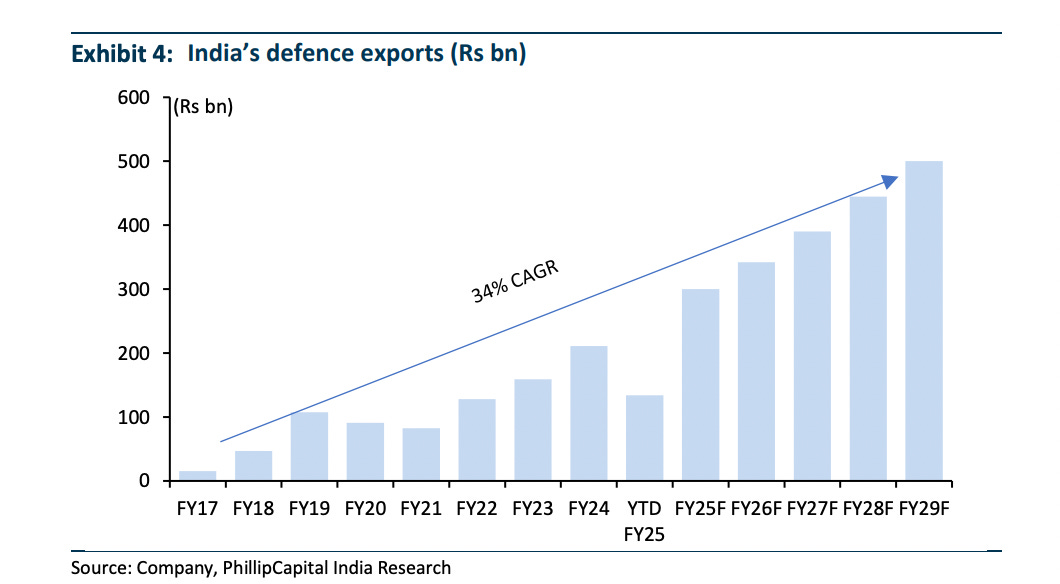

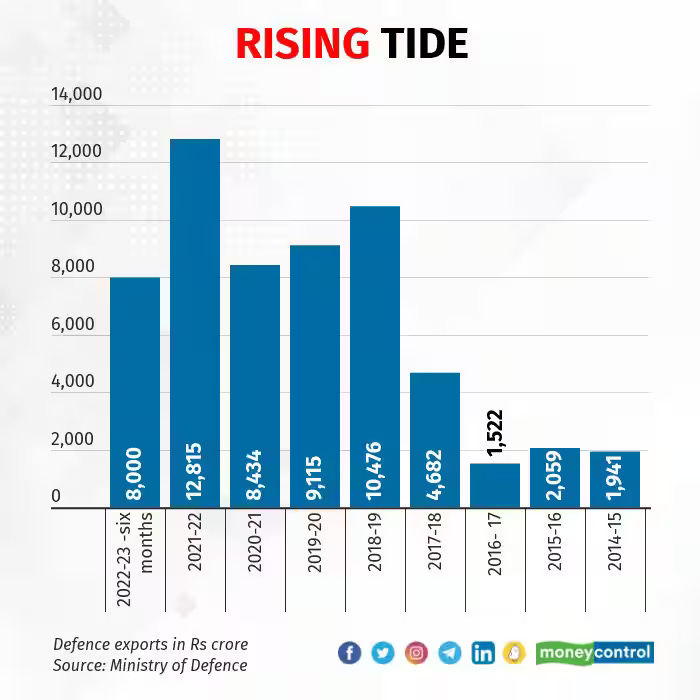

India’s defence exports have seen a meteoric rise—from ₹686 crore in FY14 to over ₹21,000 crore in FY24. This reflects a 30x jump within a decade. Products range from BrahMos missiles and artillery systems to radars and patrol boats. India now exports to over 85 countries.

Major buyers include nations in Southeast Asia, Africa, and even developed markets like the US, which sources components and sub-systems from Indian firms. This export narrative not only boosts foreign exchange but also builds strategic depth and strengthens geopolitical ties.

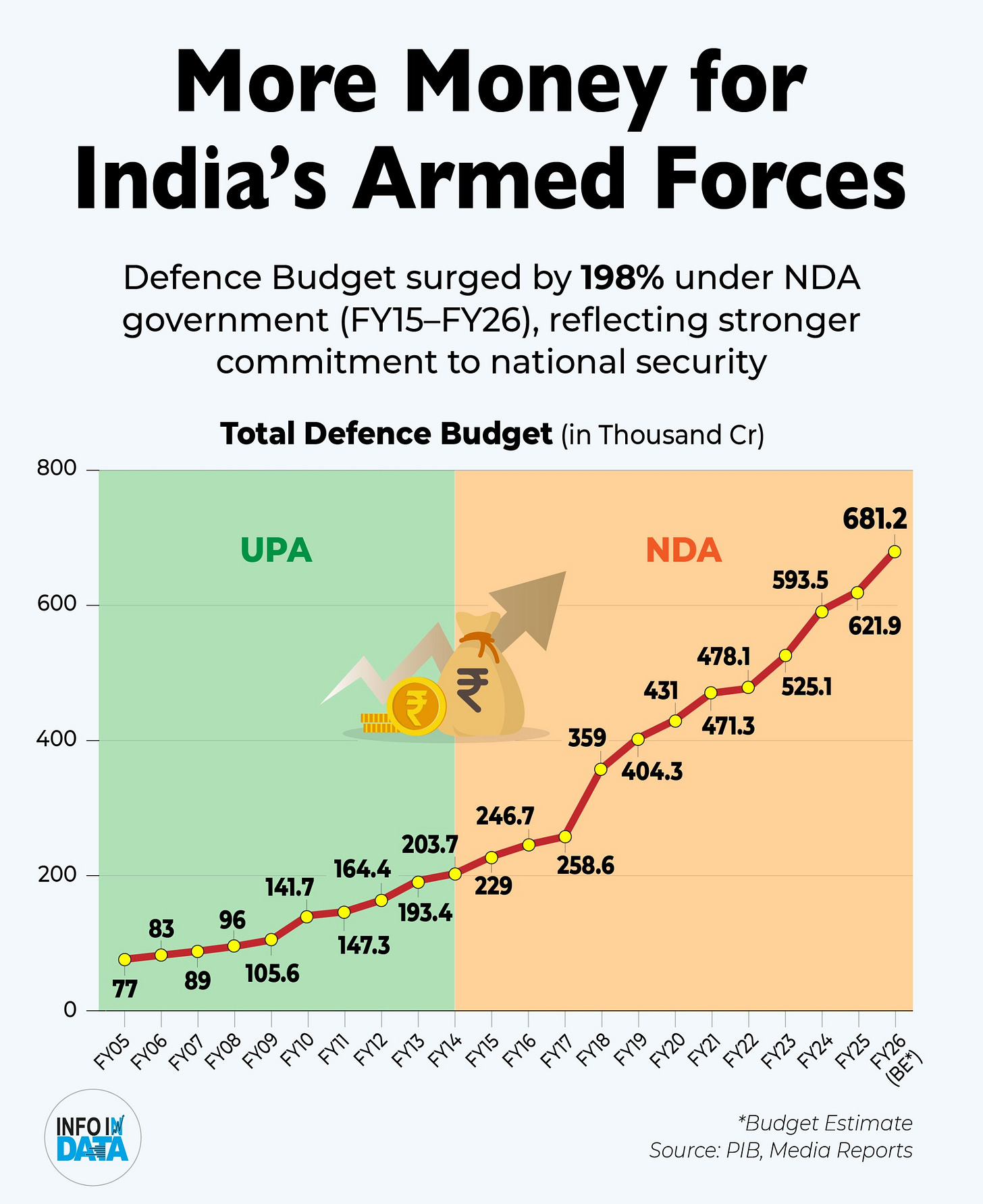

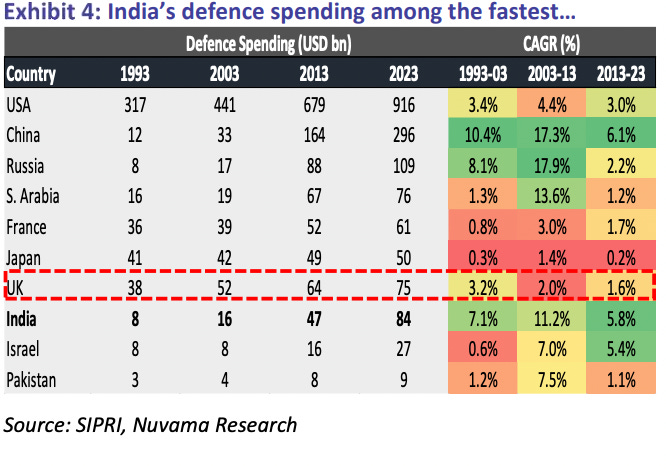

Backing the Boom: Defence Budgets and Capex Spike

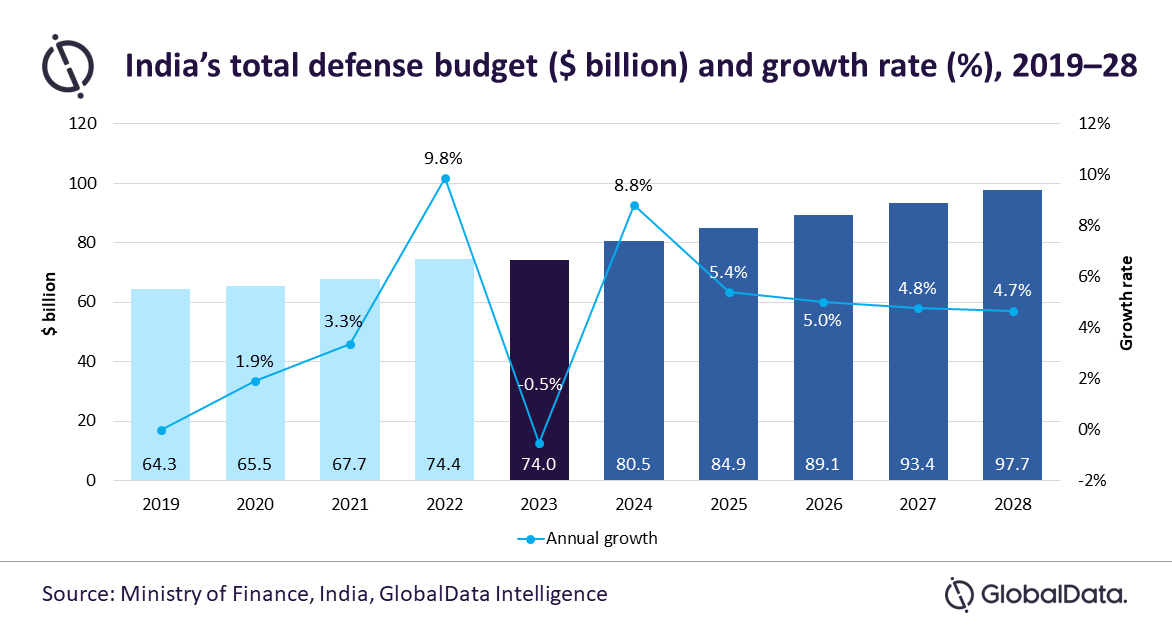

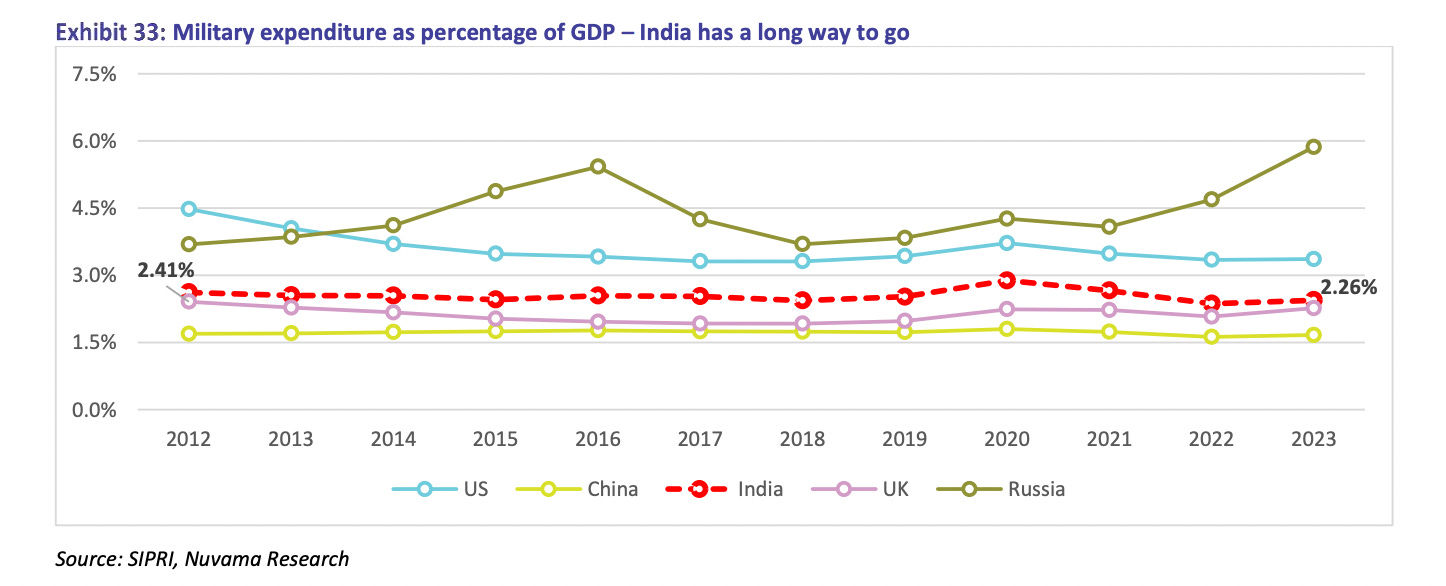

India is now the third-largest defence spender globally. More importantly, capital expenditure for new equipment and R&D has risen sharply. In FY25, ₹1.72 lakh crore was allocated for capital procurement, a record high.

This increase directly fuels Indian defence firms—whether for Tejas fighters, Arjun tanks, Pinaka rocket systems, or indigenous warships. For investors, the implication is clear: a steady stream of domestic demand backed by a robust fiscal pipeline.

The Market Speaks: Bulls in Camouflage

Over the last few years, defence stocks in India have taken off in a way few predicted. From 2020 to 2024, listed defence companies like HAL, BEL, Bharat Dynamics, and Paras Defence have seen meteoric rises—often doubling, tripling, or more. This bull run, while exciting for investors, has deeper roots than simple speculation.

What's Driving the Rally?

Several geopolitical flashpoints have catalyzed investor interest. The Indo-China standoff in Galwan (2020), the Russia-Ukraine war (2022–present), and rising tensions in the Indo-Pacific have spotlighted the need for strong domestic defence capability. As governments around the world ramped up their defence budgets, India too boosted capital outlays.

Simultaneously, the Indian government’s Atmanirbhar Bharat push and “negative import list” policy created a clear demand pipeline for domestic players. This visibility was something the sector had long lacked. Large order wins—from fighter jets to radar systems—poured in, and the market took notice.

P/E Re-Ratings and FOMO

Stocks like HAL, which once traded at 10–12x earnings, saw significant P/E re-rating as analysts reassessed growth potential. BEL, Paras Defence, Data Patterns, and others also saw valuations stretch as earnings momentum picked up and retail investors flooded in.

The Nifty India Defence Index, launched in 2023, outperformed the broader market by over 60% by mid-2024. Brokerage reports turned bullish. Defence began to be seen not just as a cyclical or policy play—but as a secular growth theme.

But is it all justified?

What’s Next? The Battle Between Fundamentals and FOMO

A Global Arms Race

Global defence spending is accelerating. The US passed a $850B defence budget for 2024. China is investing heavily in naval modernization. Europe, shocked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, is rearming at a scale not seen since the Cold War.

India’s own targets are ambitious: aiming for $5 billion in annual defence exports by 2025. While that may be optimistic, the growth trajectory is undeniable—with FY24 already crossing ₹21,000 crore (~$2.5B) in exports.

Risks to Watch

However, this is not a straight road. Risks loom large:

Budget constraints: Defence is capital-intensive. A slowdown in the economy or fiscal tightening could stall momentum.

Tech lag: While India has made strides, core technologies (e.g., jet engines, advanced sensors, AI-enabled targeting) still rely heavily on foreign partners.

Policy reversals: A change in government or global recession could alter priorities.

Execution risk: Scaling up manufacturing and maintaining quality in complex systems is no small feat.

AI, Drones, and the Next Frontier

The future battlefield will be defined by autonomy, speed, and data. AI-enabled drones, cyber defence, and space-based surveillance are critical domains. Indian startups and listed players like ideaForge, Data Patterns, and Paras Defence are making moves, but global competition is fierce.

There’s also M&A potential. As contracts grow and tech becomes the differentiator, expect consolidation. Bigger players may acquire niche startups to gain an edge.

Industry Heatmap: Who’s Who and What to Know

Here’s a breakdown of key companies driving India’s defence story:

Public Sector Giants

HAL (Hindustan Aeronautics)

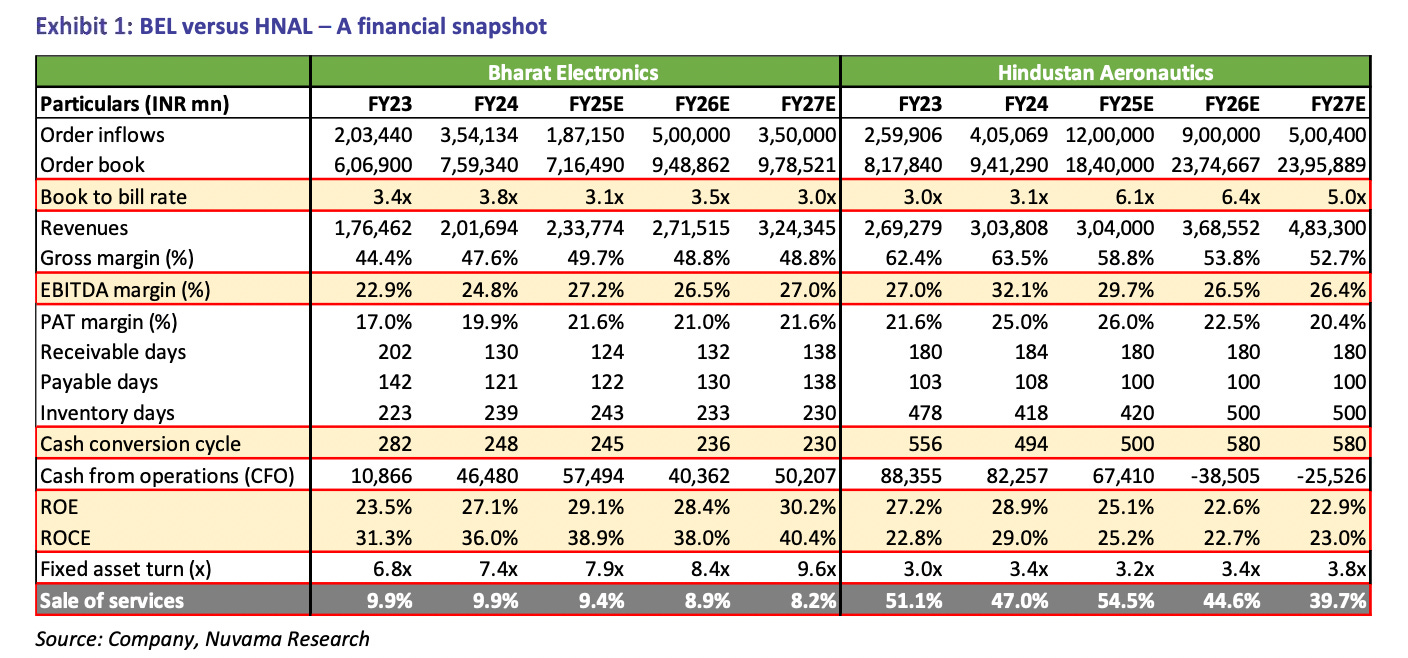

Strengths: Large order book (₹84,000+ crore), strong execution track record

Risks: Government dependency, long payment cycles, limited export footprint

BEL (Bharat Electronics)

Strengths: High margins, diversified product suite (radars, EW, avionics), growing exports

Risks: Margin compression from price pressure, over-reliance on MoD

BEML

Strengths: Focused on mobility platforms (tanks, recovery vehicles), diversification into mining & rail

Risks: Lumpy order flows, strategic disinvestment pending

Private Titans

Larsen & Toubro (L&T)

Strengths: Deep naval and missile infrastructure, global partnerships, proven track record (K9 Vajra)

Risks: Defence is a small % of overall revenue—could remain underleveraged

Tata Group (via Tata Advanced Systems & Tata Elxsi)

Strengths: Deep R&D, C-295 aircraft JV with Airbus, focus on aerospace and electronics

Risks: Limited listings—Tata’s defence verticals are mostly unlisted

Bharat Forge

Strengths: Export-ready platforms (ATAGS), dual-use infrastructure, global reach

Risks: Cyclical in nature, faces capex constraints if orders stall

Dual-Use Innovators

Paras Defence

Strengths: Focused on optics, drone systems, and R&D-heavy contracts

Risks: Very high valuation, concentrated client base

Data Patterns

Strengths: Strong order book, profitable, end-to-end capabilities in electronics

Risks: Scalability, limited past execution at large scale

Astra Microwave

Strengths: RF systems and radar subsystems, key ISRO & DRDO supplier

Risks: Slow-moving execution cycles, tech dependency

Dark Horses

Zen Technologies – Simulation and training systems, early mover in export markets

ideaForge – High-end surveillance drones, already supplying to Army, Navy

MTAR Technologies – Strategic components for missiles, reactors, and spacecraft

Each of these firms represents a different bet: some on execution, others on policy tailwinds, and a few on long-term technological capability.

Final Word: Investing in War and Peace

Is the “Peace Dividend” Over?

For decades, defence was underinvested globally. Post-Cold War optimism suggested military budgets would shrink as the world moved toward cooperation. That peace dividend is now clearly over. Strategic competition has returned.

History shows that defence booms can be long-lasting but volatile. In the US, the post-9/11 defence rally lasted over a decade, followed by stagnation. For India, the current upcycle seems more structural than cyclical, but investors should stay nimble.

Investor Takeaways

Valuation discipline matters: Many defence stocks are now trading at 40–60x earnings. Focus on order book strength, execution, and cash flows.

Secular vs Cyclical: BEL and HAL are safer plays. Paras Defence and Data Patterns are high beta. Know what you’re buying.

Watch defence exports: Growth here reduces dependency on Indian budget cycles and boosts margins.

Profit vs Principle

Defence investing isn’t just about numbers. Some investors may wrestle with the ethical dimension of profiting from warfare and weaponry. But others argue that a strong defence supports peace—deterrence is often the best insurance.

As India walks the tightrope between security and innovation, the defence sector offers both strategic and financial returns. Whether you’re an equity investor, policy enthusiast, or simply defence-curious, this sector now demands attention.

This post is purely for informational/educational purposes. Nothing should be construed as a buy/sell recommendation.